|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

| The Smoky Addiction | ||||

|

|

HOME | SITE MAP | FORUM | CONTACT |

|

||

|

ABOUT | MOTORS | MODELS | ARCHIVE | HISTORY | STORE | FAQ | LINKS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Smoky Addiction 12

(December 2005)

by Roger Simmonds Reprinted from SAM 35 Speaks, December 2005 Afterburning There has been some pleasing feedback about the Spook and the little chuck gliders I played with as a fledgling in the early fifties. Somehow, I had forgotten what these were called, and it wasn’t until Steve Gleed jogged my memory I recalled that they were, of course, FROG ‘Aeroscouts’, and cost all of 7d (not 9d) in those far-off days. Steve also sent some photocopies of a packet and contents [right]. These gave me a real nostalgic frisson, I can tell you. John Park well remembers the instructions, “move wing forward for stunts, back for long flights”, and says he must have got through at least one Aeroscout or ‘Cutie’ or a week in 1949. Sounds about right. If an Aeroscout as our lead illustration seems incongruous, Steve suggests it might go well with a Rapier L1. Hmm … perhaps we need a Rapier L0.5! |

- Steve Gleed

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

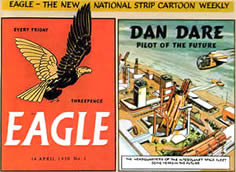

A Bill Henderson email about the Spook gave an interesting insight also into Bill’s formative flying experiences: “In 1946 I started building tailless hand launch gliders based on an article and plans by Bill Dean. The Spook is almost identical and I built and flew many of them, because they were so easy to launch and flew very well. I never saw the Keil Kraft kit.” Roy Tiller, keeper of the wonderful Bournemouth Model Aircraft Society archives, kindly provided a copy of the relevant article, ‘Flying Wings’ by W A Dean, (Model Aircraft, February 1946). The model is indeed a Spook, so it is strange that Albert Hatfull is given credit on the plan. Bill Dean’s insights into tailless design are still well worth reading – in fact so sensible and practicable are they that I wonder why he used a different method of stabilisation (a reflexed trailing edge) on his 1949 Jetwing. The prerogative of genius, I suppose. Bill Dean appears to have published more in various compendia (like the Solarbo Book of Balsa Models) and the Eagle, Meccano Magazine and RAF Flying Review than in the UK aeromodelling press during the fifties. His profile models are, in consequence, not as well known as they should be, and the Hunter below, typical of his semi-scale oeuvre (note the position of the motor) was new to Howard Metcalfe, who has a particular interest in these sorts of models, Ancient and Modern. The plan (with the maestro himself inset holding a Midge) appears courtesy of John Park. John is, like me, a child of the fifties, and we have been reminiscing about the SBAC Air shows (agreeing that 1953 was the year) and our mutual delight in the Eagle [right], which, what with Dan Dare and the superb cutaway drawings (for example the Canberra and Black Knight) understood the needs of the air (or space) minded boy.  John has returned to model jet planes quite recently, cutting his Rapier teeth, so to speak, with a Spook, before trying the less forgiving Hunter. He writes:

“The wind having died down an hour before sunset, I set out on the half-mile walk to my local flying field, equipped with Hunter, Plasticine ballast, a set of watchmaker's screwdrivers, a box of 120 mN Rapier L2s and a couple of lighters. I also took a little box of half-inch lengths of Jetex fuse as a back-up in case the Rapier fuses didn't work. There was nothing but the faintest breath of wind, blowing from the east. Hardly able to believe my luck, I hastily tried a couple of test glides with an unfired L2 in place, ballasting the nose to give a fast glide and noting the expected left turn produced by the weight and drag of the motor on that side. I take a deep breath, light the fuse, and launch … too much nose weight: the model wouldn't gain height, and turned in to the left. Reload, remove some of the Plasticine and try again … better, but still too much left turn, taking the model into the deck after ten seconds or so. Reload, and warp in a little right rudder by the old chuck-glider method of licking the fin TE and bending it between the fingers. Light the fuse; give it a few seconds for the thrust to build up, and launch firmly into a right bank … ah, that's more like it! |

- Model Aircraft, Feb. 1946 (p. 42)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“She

settles into a wide left turn, nose well up and teetering on the edge of a stall as she heads back towards me, then the speed builds up and she climbs steadily away in fifty-foot circles, drifting downwind towards the setting sun and getting to a good height – maybe a hundred feet – before burnout and a rather stally glide back to earth. I lose sight of her against the sun as she descends, but guess the total duration of the flight as around forty seconds. I blame the position of the motor, too far forward under the wing LE, for the stally glide. A stroll along the valley for a couple of hundred yards brings me to the model, which is undamaged apart from the Rapier exhaust crud that I've been warned about. The model has Halford's self-adhesive aluminium foil along the fuselage back as far as the wing TE, but the muck extends right back to the tail. Not that I'm worried – this is only a profile model, after all. There’s just time for another flight, with everything left exactly as it was. But no, this time she won't gain any height and buries her nose in the thistles just as the motor burns out. At this point I remember Dave Deadman’s DH.110 plan and article [Aeromodeller, 2000], and, having retrieved the model, I sight along the fuselage. Sure enough, the heat of the Rapier's exhaust has bowed it to the left, introducing a huge amount of left rudder and putting paid to any more flying for the day. The sun's almost down anyway – at least I had one good flight. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

“Incidentally,

a little thought about the full size DH.110 prototype always sends a chill through me. As we lived only a few miles from Farnborough, we went as a family to the 1951 SBAC show – I have clear memories of the blue-painted Avro 707B – and my father and I went to every show up to the early 60s. But for some reason we were unable to attend in 1952. It's quite possible that we simply couldn't afford it – the admission fee was five shillings for adults and half-a-crown for children, which would have amounted to fifteen bob for the whole family – but if we had been there, we'd almost certainly have been standing in the path of the debris when the 110 broke up [right]. “Thinking of all-sheet Hunter’s performance, in particular its initially sluggish climb-out, I was strongly reminded of the Keil Kraft ‘Shadow’ Attacker [right] that I flew for a whole season (1959 or 1960?) with a Jetex 50B – I used to take it along to C/L sessions, and have a couple of flights when the inevitable crash had incapacitated the ‘brick-on-a-string’. The Attacker was the same as the Hunter, structurally – fuselage of eighth sheet, wing and tail of sixteenth – and the motor was mounted on the left side of the fuselage. It flew nicely enough, but was not at all inclined to soar away into the blue as, say, the Vulture did. I've always believed that this was due to the flat-plate wing, and that just a little bit of camber would make all the difference. The fuselage warping problem did not occur with Jetex as the exhaust was much cooler and quite a bit of it was just steam. Still, having satisfied my curiosity, I don't think I'll persist with the Hunter, or any of the other Jetex 50 designs with the motor mounted on the side of a sheet fuselage – unless, that is, I can come up with a way to get over the problem of heat distortion.” Rapier exhaust, then, needs to be directed well away from the fuselage – indeed from any surfaces – and side mounting a Rapier is not advisable, unless, as with Dave Deadman’s little DH.110, it is well to the rear. Incidentally, this L1 powered model goes wonderfully if the 3° of tailplane incidence (unfortunately omitted from the plan) are added. If not mounted at the rear, then, a Rapier needs to be either high up or low down: bit of a problem for a scale model. |

- Kenneth Johanssen

- Model Aircraft, Sep. 1955

|

|||||

|

One solution is to put the Rapier well below the fuselage in a (perhaps fanciful and non-scale) ‘rocket pack’ or drop tank, as Howard Metcalfe has with his new profile Hunter [right]. It also, says Howard, gives one something to hold whist launching. Note the Hunter’s wing has a proper, though of necessity thin, aerofoil. Howard creates his models’ intricate colour schemes and decoration with a domestic version of AutoCAD; the results are printed in reverse on heat transfer paper and ironed directly on to the wood. Considerable heat is apparently required for this latter process, (the phrase ‘cotton setting’ springs to mind) so it is not suitable for Depron. It cannot accommodate complex curves either; but, as can be seen with the Hunter, the results are most attractive. As his computer expertise grows, Howard is experimenting with even more complex detailing and shading, and, in his latest Mirage delta, achieves a trompe l’œil effect that adds much to the realism of these artful creations. |

- Howard Metcalfe

|

|||||

Please contact Howard if you would like details of this latest Hunter or any of his other all-sheet models; the Hawk [below right], the Harrier, the Depron ‘semi profile’ T-38 Talon [right], and, coming soon, the brightly coloured Lansen catapult glider featured in the (Jet)X Files, August 2004.

- Howard’s re-creation of the Jetex Wren

Le Pfufp, Glouglou and la Saga des Jets |

|

Howard’s Depron ‘semi profile’ T-38 Talon

- Howard Metcalfe

- Margaret Webb

|

||||

|

Following the appearance of Georges Bougueret and his bi-poutre in September’s column, I received not one, but two, packages of French Goodies from Jean Thiry, a SAM Speaks reader who lives in Nancy. Jean’s first letter contained a copy of ‘La Saga des “Jets”’ [sic]. This, first published in the Bulletin de Liaison of the ‘Association des Amateurs d'Aéromodèles Anciens’ in 1992, included the 3-view on the right. Jean comments that whilst it is not exactly that of the 1946 rocket plane, it is very similar. ‘La Saga des “Jets”’ (the jet saga) describes the activities of Jaques Lerat and others just after WW II. John Miller Crawford and I have done our best to make the translation below readable whilst retaining the flavour of the somewhat idiosyncratic (to say the least) French of the original. “Following the first proving trials with a tricycle-equipped UPCF 100 and a UPCF IV powered by a rocket fixed with bands above the centre of the wing, the model that was demonstrated at Issy-les-Moulineaux was the UPCF 200 [right]. In the wake of an explosion [!], the fuselage was lengthened to lighten the ballast required. The 210 [right] used the same fore-section of the fuselage, but its after-section was a single boom made from hard wood. The same wingspan and area was used, but with a slight camber to increase the lift. The cessation of the manufacture of motors giving 200 g thrust for 20 seconds halted the development of this type of machine. “October 1946 saw the public appearance of the Aérolithe, at a meeting held to attempt speed records. It had a fuselage that was half sheet and half stick, in the same familiar configuration used on Bizuth and Tapir. With the Ruggieri Company's new motor positioned atop the wing in order to control a tendency to stall, it made a good showing, recording ratios of 3 to 4 despite the unfavourable weather. All the same, enthusiasm was fading and October 9 proved to be its sole outing. “It took the appearance of Jetex in France to rekindle interest in rocket propulsion. Three models from the Jetex generation were: Pfufp, taking its name from the sound of the Jetex 50 motor; Glouglou, designed for the Jetex 100 ('Glouglou' came from the sound of the Jetex motor operating under water in the pond where the model had ended its initial test flight); and Soucoupe ['Saucer'], which, with its circular wing, took to the air in rather acrobatic gyrations.” Jaques Lerat’s UPCF 200 is shown on the right; and no, I don’t know what ‘UPCF’ stands for either. The references to the Aérolithe, Bisuth and Tapir in the saga will have to remain tantalising, I’m afraid, as there are neither photos nor details of any of these designs, nor of the Soucoupe, or the amusingly onomatopoeic Glouglou. The all but unpronounceable Pfupf is, in contrast, quite well known: P Maillard’s design was first published in Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion (MRA), December 1951, and, modified and redrawn for L1 or L2 by our own Graham Knight, the plan has been available on the Jetex.org website for some time. This simple model has proved a popular and effective introduction not only to Rapier flying, but also to the art of making (and covering) built-up wings. Jean’s second, and heavier, letter contained a grand selection of plans from MRA. Some, like the Mosca, Puk, and Yak 25 have appeared in SAM Speaks before; the Jolly Frolic and Georges Chaulet’s Hélicomète are also familiar, but I definitely had not seen two of the more ambitious models before – a Starfighter and (oh joy!) a Leduc 022. These, the creations of Henri Tardif, but published by Maurice Mouton, are most unusual in that the enclosed motors are not Jetmasters but Jetex 100s, which were probably unavailable commercially at that time. These fire into Jetex 50-size augmenter tubes. The Starfighter (span 14.5'', length 24'', weight 68 g) is more reminiscent of a Lancer than an F-104, and has more dihedral than the contemporaneous (and better engineered) Jetex (Sebel) Tailored model. The unique Leduc 022 (13.5'' span, 18.5'' length, weight 68g) is more true to scale. Mouton implies these are simple models; they are anything but, and though the Leduc 022’s fuselage is a substantial rolled balsa tube, that of the Starfighter is a monocoque carved from solid. “Happy landings … Amusez-vous bien”, quips a jolly M. Mouton at the end of his articles, but M.Tardif (right) looks quite pensive. Trimming either model cannot have been easy. As experiments with TD 010 ducted fans are hinted at in the text, they may well have been underpowered. Below (left): side view of Henri Tardif’s F-104 Starfighter for Jetex 100. Below (right): detail of motor installation in the Leduc 022; note the non-standard ‘bell’ and that the jet nozzle is not only some distance from the mouth of the bell but also not quite central to the augmenter tube. This arrangement cannot have been efficient, and one wonders why Tardif didn’t use a Jetmaster, or the smaller, lighter (and only slightly less powerful) 50C. |

Georges Bougeret’s Motomodèle Bi-poutre  Jacques Lerat's UCPF 200 and 210

- AAAA Bulletin de Liaison, 1992

Jacques Lerat's UCPF 200 at Issy-les-Moulineaux, 1946. Lerat kept the faith and published on Jetex

- AAAA Bulletin de Liaison, 1992

A recent example of Maillard’s 1951 Pfufp, as modified and redrawn by Graham Knight for L1/L2

- Graham Knight

A thoughtful and unamused M. Tardif contemplates what to do next with his F-104

- Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion, June 1963 (p. 10)

|

|||||

- Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion, June 1963

|

- Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion, Oct. 1963 (p. 10)

|

|||||

The dihedral is of course excessive, and though the structure is quite substantial and more than a little ‘agricultural’, a weight of 68 g, the same as the Starfighter, is claimed. The Leduc 022 (for which, unfortunately, we have no photo) is nonetheless an attractive model; its size is compatible with a Rapier L3 and it would make a nice stable-mate for my Leduc 021. “Build it as light as possible – as always, that’s the secret of top performances”, advises M. Mouton. Onwards and Upwards … or Perchlorate ad Astra |

|

Tardif’s Leduc 022

- Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion, Oct 1963 (p. 8)

|

||||

|

It may be wondered why, given that we have a definitive history of FROG models, there is no equivalent Jetex book, or at least, a ‘History of rocket propelled models’ similar to La Grande Histoire des Petits Avions. Yes, … er, … well, … to start with, there is the sheer weight of material. It is more a question off what to leave out rather than what to put in, and it is growing all the time. For example, Ray Tiller, while looking up the Bill Dean Flying Wing reference, found a series of articles published in Model Aircraft between February and May 1946, ‘Rocket Propulsion for Model Aircraft’ by Kenneth W Gatland. These were unexpected, to say the least – I thought I had researched that period pretty well. Somewhat disappointingly, given the title and that these were in Model Aircraft, not Meccano Magazine, Gatland concentrates on German and American research with “aerodynamical” models and guided missiles, so there is little of real relevance to aeromodelling. Howard Boys’ experiments are discussed, albeit briefly, but there is nothing about George Bougueret, Jaques Lerat, or, even, (unforgivably) Joe Mansour and his target drones. Oh well, at least there are some nice illustrations and the futuristic rocket-glider above right is worthy of another airing after nearly sixty years. Jean Thiry’s letters and Roy Tiller’s serendipitous discoveries show how much comparatively unknown stuff could still be out there. Another aspect of our progress into the past is the internet, where hitherto rare historical documents will become more accessible – the Wilmot Mansour patents, for example, now available on the Jetex.org site. These, whilst not exactly a riveting read, are well worth perusing, and include details of a Rapier-like cardboard-bodied progenitor, propellant formulations, ignition and operating temperatures and pressures, and solve an interesting puzzle: why were early motor casings thinner at the top and the first Jetex 50 ribbed? |

- Model Aircraft, 1946

|

|||||

|

So, If I have a regret about putting down (or is that unplugging?) my word processor after this final thrilling episode of the Smoky Addiction it is this: we are, thanks to Information Technology and the spread of emails and internet sites, in an exciting period of discovery, and there will be many old, but new (if you see what I mean) aspects of the history of rocket-propelled models to explore. |

||||||

|

But a definitive history, or even a saga, of rocket and jet propelled models requires an historian more assiduous in tracking down sources and competent to ‘surf the net’ than I will ever l be. My articles – the word ‘gallimaufries’ comes to mind – could never be a proper and scholarly record of our noble addiction. I have merely tried to celebrate the reactionary renaissance, encourage vintage fliers to try Rapiers and the new Rapier generation to build more of the wonderful old designs, and thus preserve the Jetex (and pre-Jetex) tradition. In conclusion, I owe a special debt to Andy Blackwell, who has always such a great encouragement; but I must thank also, amongst many others, Bert Judge, Pete Cock, Mike Ingram, Dick Twomey, Bill Henderson, Sten Persson, Jean Thiry, Ron Knight, Pete Smart, Richard Crossley, Chris Strachan, Steve Bage and of course, Ben Nead and John Miller Crawford, for all the plans, articles, ideas and stimulation they have provided so generously. |

- Roger Simmonds

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgements - Article: Roger Simmonds - Illustrations: Roger Simmonds, Steve Gleed, MAAC archives via Bill Henderson, Howard Metcalfe, Bruce Ogden, John Park, Ray Tiller, Jean Thiry |

|

|

|

|

ABOUT | MOTORS | MODELS | ARCHIVE | HISTORY | STORE | FAQ | LINKS |

|

|

Terms of Use

|

Queries? Corrections? Additions?

Please

contact us.

|

|