|

|

|

|||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

| ARCHIVE: Jetex Tailored Models | ||||

|

|

HOME | SITE MAP | FORUM | CONTACT |

|

||

|

ABOUT | MOTORS | MODELS | ARCHIVE | HISTORY | STORE | FAQ | LINKS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The early Wilmot Mansour & Co (‘Jetex’) scale models included a Gloster Meteor, De Havilland Vampire (right) and Avro 707B. These are somewhat disappointing designs with, for example, extended booms (on the Vampire), excessive dihedral, and exposed motors without troughs. Joe Mansour, the guiding genius behind Jetex, was obviously dissatisfied with these, and, drawing on his experience with moulded paper models, produced the ‘Zyra’ Space Ship to coincide with the film, “When Worlds Collide”. This model had a moulded balsa shell, so it was the first essay in Tailored technology, but as a flying design it was not altogether successful, though it was quite popular at the time. |

The “somewhat disappointing” Jetex Vampire

- Model Aircraft, May 1951

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A A (Bert) Judge, the 1934 Wakefield winner, joined Joe Mansour as Chief Designer in early 1952, followed by Joe Mansour was, according to Bert Judge, “Something of a genius, a very clever chap and could do things you would think were impossible”. He wanted to make a Hunter, and following the development of the augmenter tube and Jetmaster motor in liaison with N R Walker of the LSARA, Bert Judge designed and built a ‘proof of concept’ model with an enclosed motor and a traditional built-up fuselage and wing (above right and below). |

|

Jean Deane (Bill had the spelling slightly wrong), of the Jetex staff, with the prototype Tailored Hunter

- Model Aircraft, Dec. 1952 (p.574)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He remembers taking it out on its very first flight and lighting the fuse at the bottom of the tube with a cigarette: “We launched it off and it flew quite steadily for a bit. Then it went up and did a marvellous loop and eventually flattened itself out and landed safely. For the first test flight it wasn’t bad, and with a minor adjustment on the tailplane it was OK.” Bert says of the Hunter, “It wasn’t exact scale because the wing area was increased a bit, as I didn’t think there was enough area for a model … but I think that was a mistake. I’d used a wing section other than Clark Y for the first time because I wanted to get the shape right so that the model looked right. That Hunter had a marvellous flat glide. The next thing was to design a kit (which retained the built-up wing) and check that it flew like the original, which luckily it did. I can’t remember making a dummy structure – we went straight ahead and did the master for the tools. They were cast in mazak, a low melting point zinc based alloy.”

- Model Aircraft, Mar. 1954

Following this success, the Swift (above) and the smaller ‘Mach 1+’ models for the 50B or 50C joined them over the next eight years, as this table shows:

Tailored Kits, 1952-1960

|

Jean Deane (now Jean Rolls) poses with a production Tailored Hunter at the Jetex Commemoration festivities in 2005

- Roger Simmonds

Bert Judge with the prototype Tailored Hunter for Jetmaster (The original caption read: “The Hawker Hunter toy: it can fly at 70 to 80 miles an hour and give anyone watching a real thrill. The rocket is inoffensive and can propel the plane for several minutes.”)

- Everybody’s Magazine, 1953

An anonymous hand of a Jetex design team member holds the prototype Tailored Super Sabre

- Mike Ingram archive

Folland Gnat for Jetex 50B

- Roger Simmonds

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

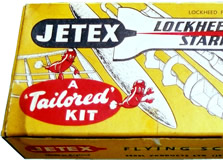

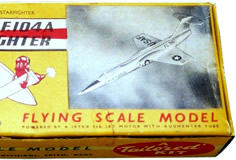

Tailored Starfighter kit

- Roger Simmonds

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

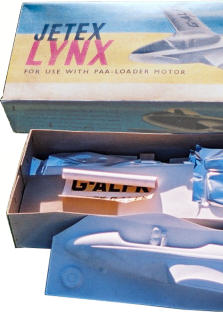

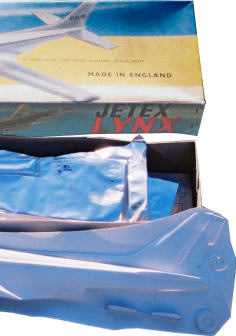

Mike Ingram left soon after designing the Fairey Delta 2, and Ron Pasco, under Bert’s direction, was responsible for the Starfighter and Crusader. Peter Cock’s Delta Interceptor for 50B and the Dan Dare Space Ship and later Jetnik for 50R also used what could be called ‘Tailored technology’, but these models are outside the scope of this article. Some prototypes never became kits;, for example, there was a Gloster Javelin to join the Hunter and Swift, but the 24" span delta proved too large and draggy for the augmented Jetmaster (right). A great pity. The models became more sophisticated and ambitious over the years and many small refinements were made. For example, the Jetmaster Hunter had vulnerable fixed wings, whilst the Swift wings could slide off their tabs in a hard arrival. The semi scale Lynx featured a vacuum-formed plastic fuselage and more remarkably, a shiny aluminised plastic wing covering complete with simulated rivets! Both the Starfighter and Crusader had thrust deflectors and moveable control surfaces. Most of the smaller models had solid sheet wings, but the Hunter (below) had a built-up structure with a single full depth spar and ribs covered in |

|

Tailored Javelin protoytype (1957)

- Mike Ingram

Crumbling remains of the unkitted Javelin (2004)

- Roger Simmonds

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Production techniques also varied slightly over the years, though after the Voodoo (which had doped tissue on a single balsa sheet) the method of producing the shells remained constant: two sheets of very light balsa were placed in female moulds with a thin sheet of heat sensitive glue in between. Small darts could be made to accommodate extreme compound curves, for example at the Swift nose, and a male mould was applied with heat to fix the shape. The shells were quite fragile before attachment to the fuselage formers, but made for a light stiff and realistic fuselage after assembly. |

- Royal Air Force Flying Review, Dec. 1954 (p. 60)

- Aeromodeller, Sep. 1954 (p. 449)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

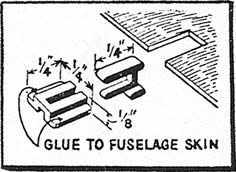

The kits were beautifully presented and set standards in prefabrication, with nicely die cut parts, fuselage shells, a clever catch for the motor hatch (right), an augmenter tube (though no motor) decals, plan, glue, and a most ingeniously designed assembly jig made of heavy cardboard. This, the work of Joe Mansour, was necessary for the accurate construction of the fuselage and alignment of the flying surfaces. The Jetmaster models were enthusiastically reviewed and their innovative nature widely praised. For example, MA, in June 1953, said the Hunter was, “one of the finest model aircraft in the world … deserves top marks in its class”, and the Swift was called, “the world’s best” and “top value for money” (MA, March 1954). The first Mach 1+ models were also praised: “the result is a model with solid realism but a total weight well within the values required for a successful model … short of being a very poor modeller (one) cannot fail to end up with a professional looking model.” It was admitted however that they were not kits to be hurried, and building “was at times quite intricate”. Curiously, there were no comments on their flying abilities. The models were all very appealing ‘nose pressed against the window’ attractions for small boys of the time, in looks superior to the contemporary ‘Flying Scale’ Keil Kraft and Skyleada models, and, it must be added, to most of today’s Rapier powered models. However, as beautiful and attractive to young modellers as these kits were, they were never cheap or suitable for beginners, and though both Voodoo and F.D.2 (right) are reported as “wonderful fliers”, many found other models difficult to build and all but impossible to trim beyond an extended glide. This is attested by quite a few comments from SAM members like, “they were beyond me”, or, the P.1A (right) “needed to be treated like a chuckie”. Joining the fuselage shells with quick drying balsa cement was in particular a somewhat fraught procedure. Even a gifted modeller like Mike Woodhouse told me, “they were a b**st**d to build and none flew very well in the conventional sense … but perhaps I could do better now”. However, they were not impossible, and Bert Judge and Mike Ingram gave many successful demonstrations of the larger models, and said they rarely had a crash. Bert has assured me that all his models were thoroughly tested and flew well. I had doubts especially about the F-104 Starfighter, but Ron Pasco in a letter says of the Starfighter, “it was like a rocket, it really did motor in a straight line, so you had to be careful where you pointed it. Of course it came to earth quickly when the power cut off”. The Crusader (below), he says, “flew quite well, though accuracy in building was very important, otherwise it would crash at the first attempt”. Overall, it is difficult to escape the impression that only experts had real success with most of the models.

|

Hatch mechanism

- Aeromodeller, Sep. 1954 (p. 449)

Jetex publicity photo of the Fairey F.D.2

- Mike Ingram archive

Jetex publicity photo of the English Electric P.1A

- Mike Ingram archive

Crusader kit box

- Roger Simmonds

From the first of the breed … (a Voodoo kit as sold in the US as an ‘Aero-formed’ model – this example changed hands on eBay in December 2005 for $US 56.55)

- eBay vendor (antiquemallrat)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

- Roger Simmonds

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Model Aircraft, 1955

The larger Hunter and Swift (above) were perhaps more reliable flying models. Both were low drag designs with nice wing sections and surprising glides. Bert Judge (right, with Hunter) avers that the secret with these models was to keep the weight under 4½ oz, but this not easy to achieve with inexpert building and lashings of pale green eau de nil dope on that Hunter! Unfortunately, the Jetmaster too was another factor. It needed careful handling to deliver its rated thrust, and the usual Hunter flight pattern, according to SAM member David Simmonds, was a short straight climb to 12 –15 feet, though in realistic fashion. To quote from his reminiscences: |

At the Jetex testing ground, Bert Judge holds a Jetmaster Hunter with Peter Cock looking on

- Mike Ingram archive

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

“The Hunter was (still is) my favourite jet fighter and I finished it in the prototype ‘eau de nil’ pale green finish. The Hunter flew very well, but only climbed to about 12-15 feet in a straight line, looking extremely realistic and with surprisingly great glide. I lost this model one hot summer’s day. I had been experimenting with putting ‘re-heat’ in the motor by cutting a fuel pellet in half and winding some fuse between the halves! It worked after a fashion, and when the second fuse ignited, the model was already at about 10 feet. It shot to the highest it had ever been, gliding straight over a nice slope on my flying field, over the fence and into the middle of a field of standing wheat. I did eventually get it back as I was friendly with the farmer and he assured me that he would look out for it at harvest time, which he did. By then it was in a sorry state and it never flew again.” Bert Judge also tells a nice story that implies the Jetmaster models were somewhat underpowered: “Mike (Ingram) built a Swift. It was a standard kit and he altered the motor mount for a Jetex 200, to take advantage of the greater thrust and duration. We took it over the golf course. It was a very smooth flight, a beautiful flight … it climbed to the highest we had seen and went ‘out of sight’. I don’t remember we ever got it back.” With Jetex models, as with any others, a good power to weight ratio is necessary for a consistent performance not over-dependent on vagaries of launch, wind gusts and the like. |

An anonymous hand of a Jetex design team member holds a Jetmaster Hunter aloft

- Mike Ingram archive

A member of the Jetex design team with a Jetmaster Swift

- Mike Ingram archive

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

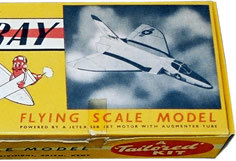

Perhaps the Tailored models were not the commercial success they could have been, though many were exported, especially to the US. Edward Jones has commented on their impact, “Tailored models won high praise from expert modellers, being accurate, well performing and ingeniously designed.” Not long afterwards (Dec. 1954) Top Flight produced their ‘Jig Time’ models for catapult and Jetex (right). These were designed by Carl Goldberg, and included a Skyrocket and an F-86 Sabre. These kits included many moulded plastic parts and the ‘superform’ balsa fuselage shells. According to the advertisements these were “die cut for an exact fit … then magically and permanently pre-formed to actual rounded contours!” These did not, however, feature an augmenter tube. Independent modellers like Paul del Gatto were inspired to design an XF-82 for augmented Jetmaster or Scorpion (1957) and to great heights of multi-motor inventiveness with his Bomarc. Gene Thomas published a Matador for augmented Scorpion (1958). It is interesting that in the US the higher powered Scorpion was favoured over the over the lower rated Jetmaster. In France, André Dautin was very quick off the mark with a YF-102 for augmented Jetmaster, published in Le Modèle Réduit d’avion, April 1954. |

- Model Airplane News, Dec. 1954

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

- Mike Ingram

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nevertheless the models were inspirational to all those who ever saw them (there is a nice anecdote of Phil Smith’s response to the Hunter in Vic Westcar’s autobiography in SAM Speaks), and it would be good to see them flying again. This presents, however, several challenges. It was thought that the Rapier motors with their bluff end and hot and dirty exhaust were incompatible with augmenter tubes, but Tony Betts’ Folland Midge for L2 HP was a wonderful flier until its demise in that bane of models with enclosed motors, the onboard fire. It would appear that the cooling air through the tube protects the aluminium, and the lack of streamlining around the nozzle is inconsequential (a point also made by the use of a Jetex 200 in a Jetmaster Swift – see above). More serious is the lack of a modern motor equivalent to the Jetmaster/Jetex 200; replicas of the larger models will have to rely on old motors and old fuel. Fortunately, a PAA-Loader can still be found comparatively cheaply. |

- Aeromodeller, Mar. 1955 (p. 149)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Old kits and built up examples of tailored models do turn up from time to time as lofts are cleared. For example, Andy Blackwell acquired a Swift that had been a child’s plaything and in a very sorry state, with broken wings and tailplane mended with builder’s tape. It had been subjected not only to multiple coats of thick blue paint but also to the indignity of Japanese markings! It weighed 7½ oz. Andy’s meticulous restoration involved making new wings and tail, but the most arduous task was to remove the paint without destroying the delicate balsa fuselage shell. After some trials, Andy found Rustin’s ‘Strypit’ to be just the ticket, and was able to get down to the bare wood (and as he says, ‘sometimes beyond’) with wire wool and elbow grease. Lindsey Smith moulded a beautiful new canopy, and, with Starspan covering,) the model weighs 4 oz with motor mount, which is about right. Andy will not decorate it until after its first flight. He is hoping to use one of his antique Jetmasters with original ICI fuel, though he does have the option of fitting a Jetex 200 if more ‘poke’ is required. Chris Strachan, who knew of the Jetmaster Tailored models, but had not handled one in the flesh, remarked how large and impressive the Swift was, especially to someone used to L2 powered models (see illustrations). Unbuilt kits do turn up from time to time, but these are generally quite rare and too precious to build. Even if one wished to build these fifty year-old kits, the delicate shells do not usually age very well, and can become brittle and distorted. Jigs too may be missing, as the wise stored these separately (the cardboard is heavy and could break the fragile balsa shells in normal storage conditions). It may be best, then, to start from scratch. The lack of fuselage formers and plans is not too much of a hindrance to an experienced modeller, but the recreation of the fuselage shells is not easy. One strategy, building a solid balsa and hollowing this out is perfectly possible, and indeed this is what John Nesbitt did in the 80s with his Hunter for Jetmaster, but this procedure is messy and inelegant to say the least. The creation of a male mould and covering this with balsa strips soaked in water/ammonia is also feasible, if still a trifle messy. There are moulding techniques out there with foam and Kevlar used by our free flight contest colleagues which may be pertinent, but best of all would be the recreation of a male and female mould. This is however, beyond the amateur resources of most of us, and perhaps not really what the average SAM member is about. It is one of the aims of this article to gauge the level of interest in these models and see if the resources of a modern manufacturer can be used. |

Andy Blackwell’s restored Jetex Tailored Swift

- Andy Blackwell

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

- Roger Simmonds

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgements - Article: Roger Simmonds, who thanks Bert Judge, Mike Ingram and Pete Cock for much of the information contained in the article. - Illustrations: Mike Ingram, Andy Blackwell, Terry KIdd, Roger Simmonds, MAAC archives via Bill Henderson |

|

|

|

|

ABOUT | MOTORS | MODELS | ARCHIVE | HISTORY | STORE | FAQ | LINKS |

|

|

Terms of Use

|

Queries? Corrections? Additions?

Please

contact us.

|

|